Dr. Amit Janbandhu, Dr. Sanjay Singhal

1. Introduction

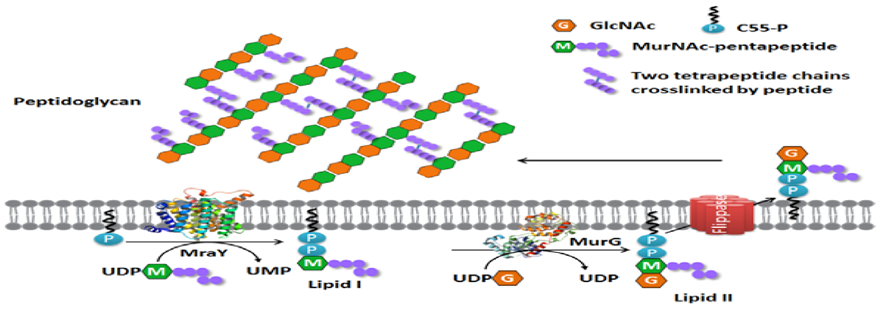

Necrotic enteritis (NE) is a significant burden on the poultry industry, causing gut damage that reduces nutrient utilization and productivity. Production losses due to NE and current control methods are estimated to cost the global broiler industry approximately USD 6 billion annually (Wade and Keyburn, 2015). These losses are associated with decreased production performance, mortality of up to 1% per day, treatment costs, and carcass condemnation due to cholangiohepatitis (Immerseel,et.al, 2004 & Timbermont, et.al,2011). Clinical and subclinical forms of NE have been recognized (Van Immerseel et al., 2004); the clinical form results in acute disease and bird mortality. Although flock health and productivity can be maintained using IFA-free practices (Parent et al., 2020), strong industry moves away from IFAs have increased the need for alternative approaches. Consequently, a wide range of feed additives and treatments have been investigated and commercialized to control NE.

NE is caused by Clostridium perfringens and primarily affects chickens from 2 weeks to 6 months of age. In humans, C. perfringens intoxications are the third most common bacterial foodborne disease after Salmonella and Campylobacter, with 359–2173 cases reported annually in the United States. Poultry and poultry products account for 30% of outbreaks, and 92% are traced to meat and poultry as a single identified food commodity (Grass et.al, 2013). Research into antibiotic alternatives that improve gut health and immune status has intensified; however, current alternatives are less effective than antibiotics in controlling NE. A greater understanding of C. perfringens virulence factors, NE pathogenesis, and host responses is required to develop effective control strategies and new supplements, as these aspects are not yet fully understood and remain under investigation.

2. Necrotic Enteritis

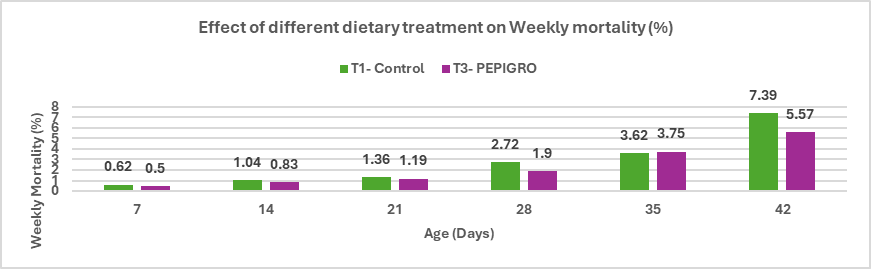

Etiology: Necrotic enteritis is caused by Clostridium perfringens, a Gram-positive, rod-shaped, anaerobic bacterium that forms oval subterminal spores. Unlike most clostridia, C. perfringens consists of relatively large, encapsulated, non-motile rods (0.6–2.4 × 1.3–9.0 µm). Colonies are smooth, round, and glistening, with an inner zone of complete hemolysis mediated by theta-toxin and an outer zone of incomplete hemolysis caused by alpha-toxin (Cato et al., 2002).

Clostridium perfringens is classified into five biotypes (A–E) based on the production of four major lethal toxins: alpha, beta, epsilon, and iota. In addition, enterotoxin (CPE) and beta2 (CPB2) toxins are considered important in enteric diseases; however, their roles in avian C. perfringens–associated enteric disease remain unclear (Crespo et al., 2007). All five types produce toxins: type A (α), type B (α, β, ε), type C (α, β), type D (α, ε), and type E (α, ι). Necrotic enteritis is primarily associated with C. perfringens types A and C caused by α and net B toxins (Fisher et al,2005)., with infections in poultry mainly caused by type A and, to a lesser extent, type C. Because type A is highly prevalent in the intestines of healthy birds, its pathogenic role remains controversial (Smedley et.al,2004). Moreover, strains isolated from NE outbreaks have not been shown to produce higher levels of alpha toxin than isolates from clinically healthy broilers.

Fig 1. Microscopic appearance of Clostridium Perfringes

Table 1: The most important C. perfringens toxins

| Toxin | Gene location | Biological activity |

| Alpha toxin | Chromosome | Cytolytic, haemolytic, dermonecrotic, Lethal |

| Beta toxin | Plasmid | Cytolytic, dermonecrotic, lethal |

| Epsilon toxin | Plasmid | Oedema in various organs: liver, kidney and central nervous system |

| Iota toxin | Plasmid | Disruption of actin cytoskeleton and cell barrier integrity |

| Beta2 toxin | Plasmid | Cytolytic, lethal |

| Enterotoxin | Chromosome/ Plasmid | Cytotoxic, lethal, causes diarrhea by leakage of water and ions |

| Theta toxin | Chromosome | Lyses red blood cells and modulates the host inflammatory response |

(Source: Wise and Siragusa et.al, 2005)

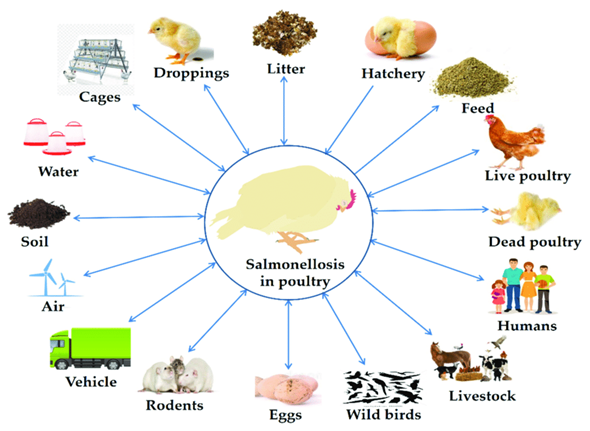

3. Epidemiology

3.1. Source of Infection and Transmission: Clostridium perfringens is a naturally occurring bacterium in poultry production environments. It is present in dust, soil, feces, feed, poultry litter, eggshell fragments, fluff, and the intestinal tract of poultry. Feces of wild birds may also contain elevated numbers of C. perfringens, further introducing the organism into poultry facilities. Environmental sampling on poultry farms detected C. perfringens on wall swabs (53%), fan swabs (46%), fly strips (43%), dirt outside entrances (43%), and boot swabs (29%), demonstrating its ubiquitous environmental presence (Craven et.al,2001). Transmission occurs primarily via the fecal–oral route and through contaminated feed, water, housing structures, insects, and direct contact between infected and susceptible birds. During necrotic enteritis (NE) outbreaks, contaminated feed or litter are considered major sources, and contaminated feed components have also been implicated. Vertical transmission is possible, as C. perfringens has been found in the yolk sac of embryonated eggs, suggesting transmission within integrated broiler operations (Craven et.al, 2003). Additionally, C. perfringens may be transmitted mechanically and/or biologically by house flies in poultry houses, contributing to NE development (Dhillon et.al,2004).

3.2. Predisposing factors

Necrotic enteritis (NE) develops when one or more predisposing factors are present, particularly intestinal mucosal damage. Damage caused by coccidial pathogens releases growth factors that promote C. perfringens proliferation in the intestinal lumen. Broilers inoculated with Eimeria spp. and fed C. perfringens–contaminated feed show higher mortality than birds fed contaminated feed alone. Physical damage from litter eating or fibrous diets may also alter the mucosa (Williams et.al,2005).

Management factors such as feeding practices, water supply, temperature control, and ventilation contribute to NE. Delayed initial feeding impairs gut-associated lymphoid tissue development. Nutritional stress from unbalanced diets, especially low energy-to-protein ratios, increases feed intake, nitrogen levels in digesta, and susceptibility to clostridial overgrowth. Diet composition strongly influences NE. Diets rich in wheat, rye, and barley contain indigestible non-starch polysaccharides that increase digesta viscosity, slow gut transit, and favor anaerobic bacteria. Broilers fed wheat-, rye-, or barley-based contaminated diets have higher mortality than those fed corn-based diets. Pelleted diets reduce intestinal C. perfringens, whereas high-protein diets (e.g., fishmeal) and bone meal increase NE risk (Kocher et.al,2003).

Immunosuppression increases NE susceptibility. Use of Infectious bursal disease (IBD) vaccines has been associated with increased NE lesion severity, even at normal doses. Stressful conditions may further predispose birds to NE, but immunosuppression is inappropriate when evaluating vaccines (Nikpiran et.al,2008).

4. Clinical Signs and Lesions

4.1. Clinical signs:

Subclinical necrotic enteritis (SNE) shows no obvious clinical signs and is usually detected under field conditions at processing plants through carcass rejection. SNE may be suspected based on reduced weight gain, poor feed conversion efficiency, increased moisture in droppings, and wet litter, most commonly at 2–5 weeks of age without increased mortality.

Clinical necrotic enteritis (NE) typically affects broiler chicks between 2–6 weeks of age and presents with sudden onset of diarrhoea and intestinal mucosal necrosis. Affected birds are depressed, anorectic, have ruffled feathers, and tend to huddle. In advanced stages, birds become laterally recumbent, immobile, and die rapidly. The disease course is usually short, and birds are often found dead without prior clinical signs. Acute signs include severe depression, reduced appetite, reluctance to move, ruffled feathers, and diarrhoea, with illness lasting only 1–2 hours [20]. Mortality in affected flocks may range from 1% to 50%.

Birds that die of NE have a foetid odor, dehydration, dark and dry pectoral muscles, and pale kidneys. The unopened intestine is darker than normal and distended due to bile-stained contents (Long, et.al,2007)

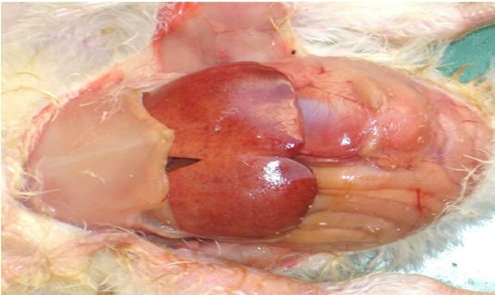

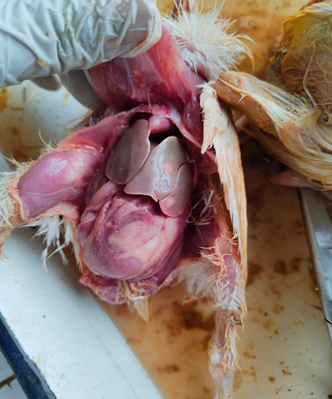

4.2. Gross lesions:

Lesions of SNE are characterized by necrotic lesions in the intestinal wall and liver, occurring in one or more intestinal regions. Mild lesions appear as small ulcers or light-yellow spots on the mucosal surface, mainly in the jejunum and ileum and less commonly in the caeca. Severe lesions may involve membranes covering large intestinal segments, including the colorectal region and caecal tonsils. Liver abnormalities, primarily enlargement and occasional congestion, are also reported.

Clinical NE is characterized by extensive mucosal necrosis of the small intestine, covered with a yellow-brown or bile-stained pseudomembrane. Gross lesions are mainly confined to the small intestine but may also involve the liver and kidneys. At necropsy, the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum are thin-walled, friable, gas-filled, and distended with dark brown fluid. Ulcers may occur singly or in aggregates. In severe cases, a fibrino-necrotic or diphtheritic membrane covers large segments, often involving two-thirds of the jejunum and ileum (McDevitt et.al,2006).

4.3. Histopathological changes:

Microscopically, NE lesions consist of coagulative necrosis at the villous apices with a clear demarcation between necrotic and viable tissue. Degeneration may extend into the submucosa. Regeneration is characterized by epithelial proliferation, connective tissue formation, and reduced goblet, columnar, and epithelial cells, resulting in short, flattened villi with reduced absorptive surface. The pseudomembrane consists of necrotic villi, inflammatory cells, and bacterial aggregates (Olkowski et.al.2008).

Fig. 2. Gross pathological changes in NE: A. Jejunum of a bird showing ballooning. B. Jejunum showing small blackish necrotic spots. C. Jejunum showing Turkish towel appearance. D. Duodenum showing congestion.

5. Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis describes the complex and dynamic host–pathogen interactions at the molecular level and is essential for developing effective control measures. Bacterial pathogenesis involves six overlapping phases: colonization, growth and proliferation, nutrient acquisition, evasion of host defenses, host tissue injury, and transmission. In rapidly growing pathogens such as Clostridium perfringens, these phases occur almost simultaneously.

Colonization requires degradation of the intestinal mucus layer, which normally acts as a physical barrier. Intestinal mucins provide binding sites for bacterial adhesins, and pathogenic C. perfringens secrete bacteriocins (perfrins) that displace commensal Clostridium species. The organism produces glycoside hydrolases and chitinases that degrade mucins, providing nutrients and enabling microcolony formation on the mucosa. Predisposing factors such as Eimeria infection stimulate inflammation, increased mucin production, and release of essential amino acids, all of which enhance C. perfringens growth and colonization (Collier et.al,2008).

Once a threshold density is reached, an Agr-like quorum-sensing system activates the VirS–VirR regulatory system and virulence genes, including NELoc-1 involved in adhesion. Degradation of the mucus layer allows pore-forming toxins to access epithelial cells. Proteolytic and collagenolytic enzymes damage the epithelium, disrupt intercellular junctions, spread through the lamina propria, and cause epithelial necrosis and sloughing. Quorum-sensing–regulated secretion of alpha toxin and perfringolysin promotes biofilm formation on the exposed submucosa, enhancing bacterial persistence and protection from host immunity and antibiotics.

Intestinal integrity depends on tight junctions, particularly claudin-3 and claudin-4, which serve as receptors for C. perfringens enterotoxin (CPE). CPE binding forms small complexes that oligomerize into large CH1 complexes, leading to pore formation in the cell membrane. These pores allow calcium influx, resulting in epithelial cell death (Chakrabarti, et.al,2005).

Gross lesions of necrotic enteritis primarily affect the jejunum and ileum, with occasional involvement of the duodenum and ceca. The intestine is thin, friable, gas-distended, and covered by a tan orange pseudomembrane, producing the characteristic “dirty Turkish towel” appearance. Pseudomembrane formation is most common in the jejunum. Subclinical necrotic enteritis is associated with hepatitis or cholangiohepatitis and gall bladder distension with flocculent material. Bile acids promote sporulation and enterotoxin production by C. perfringens, explaining the higher lesion frequency in the upper small intestine, particularly the duodenum and jejunum (Park et.al,2018).

Fig.3. Pathogenesis of necrotic enteritis in broiler chickens causes destruction of epithelial cells of intestine that leads to blood-stained diarrhea.

6. Feed Additives Used to Control Necrotic Enteritis

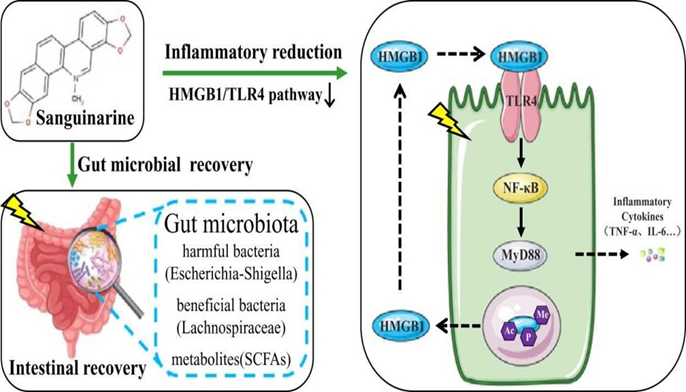

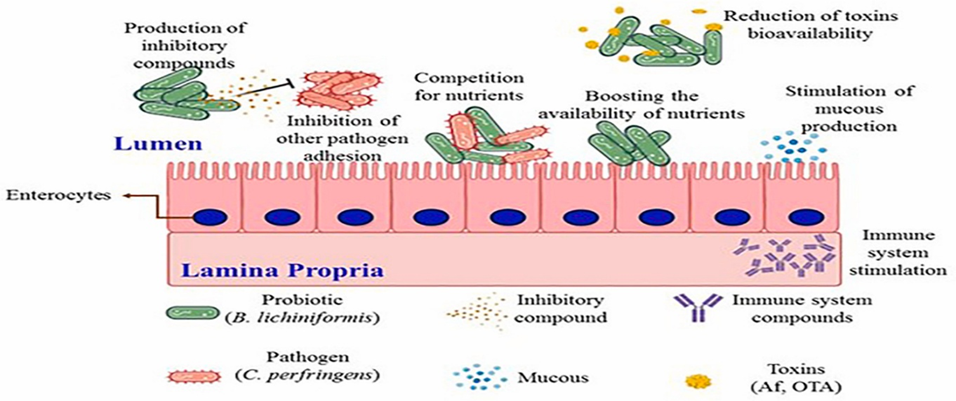

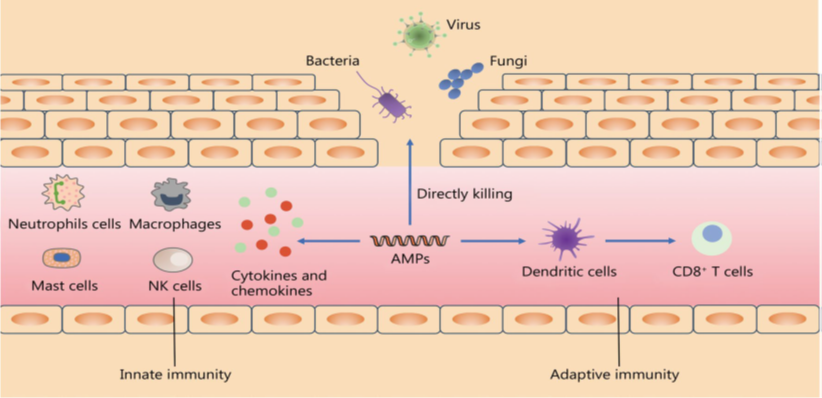

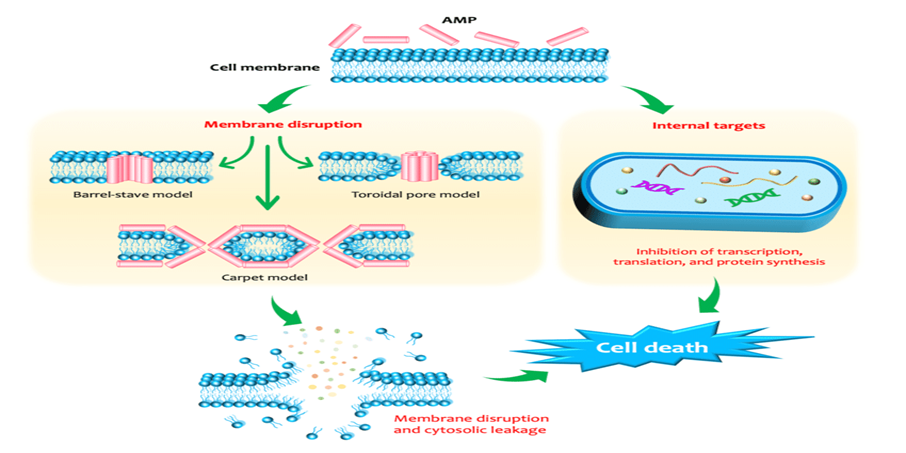

A wide range of feed additives has been studied for their effects on necrotic enteritis (NE). Most commercial additives do not target Clostridium perfringens directly but improve gut health, microbiota balance, and immune competence, often with overlapping and interconnected effects (Granstad et al., 2020). Short-chain fatty acids, particularly butyrate, provide energy to enterocytes and support beneficial microbiota. Butyrate can be supplied directly in protected form or indirectly via prebiotics, probiotics, phytobiotics, or postbiotics (Liu et al., 2021). Combinations of additives, such as fatty acids with phytobiotics, are often more effective.

Probiotics, including single or multi-strain bacteria, yeasts, or cultured cecal microbiota, can directly inhibit C. perfringens, compete for gut niches, improve microbiota composition, gut integrity, or immune function. Prebiotics, fatty acids, and phytobiotics have also been reviewed for general health and NE-specific applications (Gomez-Osorio et al., 2021).

Novel approaches include bacteriophages and their endolysins, which specifically target C. perfringens, and bacteriocins produced by bacteria for antimicrobial effects. Passive immunization using egg yolk antibodies or engineered single-chain antibodies has shown potential in reducing NE ( Gangaiah et al., 2022).

Commercial feed supplements such as StalBMD (BMD), Magnox (lincomycin), and Stalgro (enramycin) by Stallen South Asia Pvt. Ltd are also used to prevent NE caused by C. perfringens.

7) Mechanism of Action

7.1) Bacitracin Methylene Disalicylate (BMD)

Bacitracin Methylene Disalicylate (BMD) is a polypeptide antibiotic used to prevent and treat Gram-positive bacterial infections. It inhibits bacterial cell wall synthesis by blocking dephosphorylation of bactoprenol phosphate, preventing peptidoglycan transport. This disrupts cell wall formation, causing bacterial lysis. BMD is bactericidal, particularly against actively dividing Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species.

Fig.4. Bactericidal effect on growing bacteria.

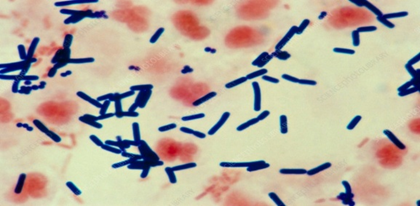

7.2) Lincomycin Hydrochloride

Lincomycin hydrochloride, a lincosamide antibiotic derived from Streptomyces lincolnensis, is used against Gram-positive and some anaerobic bacteria. Its primary mechanism is inhibition of bacterial protein synthesis by binding to the 50S ribosomal subunit, specifically at the peptidyl transferase center. This blocks the ribosomal exit tunnel, preventing elongation of polypeptide chains and halting protein synthesis, which stops bacterial growth and replication. Lincomycin may also have a secondary effect on bacterial cell wall synthesis, enhancing its overall antibacterial activity.

Fig 5. Protein synthesis inhibition within bacterial cells.

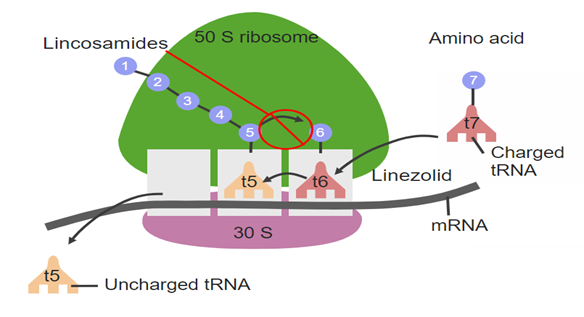

7.3. Enramycin

Enramycin acts as an inhibitor of the enzyme (MurG), which is essntial for wall biosynthesis in gram +ve bacteria. MurG catalyzes the tranglycosylation reaction in the last step of peptidoglycan biosynthesis. Hence inhibiting this step greatly compromises cell wall integrity leading to cell lysis.

Figure 6. Membrane steps of the bacterial peptidoglycan synthesis pathway.

References

Experimental induction of necrotic enteritis inbroiler chickens by Clostridium perfringens isolates from the outbreaks in Iran. Journal of Veterinary Research,2008, 63: 127-132.

Cato, P., L. George and M. Finegold, 2002. Genus c l o s t r i d i u m . B e r g e y ‘ s m a n u a l o f systematicbacteriology, USA., 2: 1141-1200.

Chakrabarti, G.; McClane, B.A. The importance of calcium influx, calpain and calmodulin for the activation of CaCo-2 cell death pathways by Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin. Cell. Microbiol. 2005, 7, 129–146. [PubMed].

Collier, C.T.; Hofacre, C.L.; Payne, A.M.; Anderson, D.B.; Kaiser, P.; Mackie, R.I.; Gaskins, H.R. Coccidia-induced mucogenesis promotes the onset of necrotic enteritis by supporting Clostridium perfringens growth. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2008, 122, 104–115. [CrossRef].

Craven, E., A. Cox, S. Bailey and E. Cosby, 2003. Incidence and tracking of Clostridium perfringensthrough an integrated broiler chicken operation.Avian Diseases, 47(3): 707-711.

Craven, E., J. Stern, S. Bailey and A. Cox, 2001. Incidence of Clostridium Perfringens in broiler chickens and their environment during production and Processing. Avian Diseases, 45: 887-896.

Crespo, R., J. Fisher, L. Shivaprasad, E. Fernández Miyakawaand A. Uzal, 2007. Toxinotypes of Clostridium perfringens isolated from sick and healthy avian species. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation, 19(3): 329-333.

Dhillon, S., P. Roy, L. Lauerman, D. Schaberg, S.Weber, D. Bandli and F. Wier, 2004. High mortality in egg layers as a result of necrotic enteritis. Avian Diseases, 48(3): 675-680.

Fisher, J., K. Miyamoto, B. Harrison, S. Akimoto, R. Sarker and A. McClane, 2005.Association of beta2 toxin production with Clostridium perfringens type A human gastrointestinal disease isolates carrying a plasmid enterotoxin gene. Molecular Microbiology, 56(3): 747-62.

Gangaiah D, Ryan V, Van Hoesel D, Mane SP, Mckinley ET, Lakshmanan N, et al. Recombinant Limosilactobacillus (Lactobacillus) delivering nanobodies against Clostridium perfringens NetB and alpha toxin confers potential protection from necrotic enteritis. Microbiologyopen 2022;11: e1270. https://doi.org/10.1002/ mbo3.1270.

Gomez-Osorio L-M, Yepes-Medina V, Ballou A, Parini M, Angel R. Short and medium chain fatty acids and their derivatives as a natural strategy in the control of necrotic enteritis and microbial homeostasis in broiler chickens. Front Vet Sci 2021; 8:773372. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2021.773372.

Granstad S, Kristoffersen AB, Benestad SL, Sjurseth SK, David B, Sørensen L, et al. Effect of feed additives as alternatives to in-feed antimicrobials on production performance and intestinal Clostridium perfringens counts in broiler chickens. Animals 2020; 10:240. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10020240.

Grass, J.E.; Gould, L.H.; Mahon, B.E. Epidemiology of foodborne disease outbreaks caused by Clostridium perfringens, United States, 1998–2010. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2013, 10, 131–136. [CrossRef] [PubMed].

Immerseel, F.V.; Buck, J.D.; Pasmans, F.; Huyghebaert, G.; Haesebrouck, F.; Ducatelle, R. Clostridium perfringens in poultry: An emerging threat for animal and public health. Avian Pathol. 2004, 33, 537–549. [CrossRef] [PubMed].

Kocher, A., 2003. Nutritional manipulation of necrotic enteritis outbreak in broilers. Recent Advances in Animal Nutrition in Australia,14: 111-116.

Liu L, Li Q, Yang Y, Guo A. Biological function of short-chain fatty acids and its regulation on intestinal health of poultry. Front Vet Sci 2021; 8:736739. https:// doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2021.736739.

Long, R., A. Barnum and R. Pettit, 2007. Necrotic enteritis in broiler chickens. Pathology and proposed pathogenesis. Canadian Journal of Comparative Medicine, 38(4): 467-474.

McDevitt, M., D. Brooker, T. Acamovic and C. Sparks, 2006. Necrotic enteritis; a continuing challenge for the poultry industry. World’s Poultry Science Journal, 62(02): 221-247.

Nikpiran, H., B. Shojadoost and M. Peighambari, Olkowski, A., C. Wojnarowicz, M. Chirino-Trejo,B. Laarveld and G. Sawicki, 2008. Sub-clinical necrotic enteritis in broiler chickens: novel etiological consideration based on ultra- structural and molecular changes in the intestinal tissue. Research in Veterinary Science, 85(3): 543-553.

Parent E, Archambault M, Moore RJ, Boulianne M. Impacts of antibiotic reduction strategies on zootechnical performances, health control, and Eimeria spp. excretion compared with conventional antibiotic programs in commercial broiler chicken flocks. Poult Sci 2020; 99:4303e13. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.psj.2020.05.037.

Park, M.; Rafii, F. Effects of bile acids and nisin on the production of enterotoxin by Clostridium perfringens in a nutrient-rich medium. Int. J. Microbiol. 2018, 2018, 7276523. [CrossRef].

Smedley Iii, G., J. Fisher, S. Sayeed, G. and A. McClane, 2004. The enteric toxins of Clostridium perfringens. In Reviews of physiology, biochemistry and pharmacology. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 152: 183-204.

Timbermont, L.; Haesebrouck, F.; Ducatelle, R.; Van Immerseel, F. Necrotic enteritis in broilers: An updated review on the pathogenesis. Avian Pathol. 2011, 40, 341–347. [CrossRef] [PubMed].

Wade B, Keyburn A. The true cost of necrotic enteritis.World Poultry 2015;31:16e7.

Williams, B., 2005. Intercurrent coccidiosis and necrotic enteritis of chickens: rational, integrated disease management by maintenance of gut integrity. Avian Pathology, 34(3): 159-180.

Wise, G. and R. Siragusa, 2005. Quantitative Detection of Clostridium perfringens in the Fowl Gastrointestinal Tract by Real-Time PCR. Applied Environmental Microbiology, 71: 3911-3916.