Dr. Amit Janbandhu, Dr. Sanjay Singhal

Abstract

The progressive ban on in-feed antibiotic growth promoters (AGPs) has accelerated the need for efficacious phytogenic alternatives capable of sustaining growth and intestinal health in modern broiler production. PHYTOGIC, a standardized phytogenic formulation derived from Macleaya cordata extract and enriched with benzylisoquinoline alkaloids (primarily sanguinarine and chelerythrine), exhibits potent antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activity, including suppression of the HMGB1–TLR4–NF-κB axis. This field study investigated the effects of dietary PHYTOGIC on growth performance of commercial Vencobb 430 broilers raised on deep litter under high ambient temperature stress (42–45 °C). A total of 36,000 chicks were allocated to two treatments: a basal diet (T1) and the basal diet supplemented with PHYTOGIC at 150 g/ton (T2). Performance indicators, including body weight, feed intake (FI), feed conversion ratio (FCR), corrected FCR (CFCR), and mortality, were monitored over a 42-day production cycle. PHYTOGIC supplementation significantly improved final body weight (2291 g vs. 2110 g; +8.22%) and feed efficiency (FCR: 1.75 vs. 1.80; CFCR: 1.67 vs. 1.77), accompanied by a moderate increase in FI (+5.50%). Mortality remained statistically comparable between groups, indicating no detrimental physiological effects. These results demonstrate that PHYTOGIC enhances nutrient utilization and growth performance under challenging production conditions, supporting its potential as a viable phytogenic replacement for AGPs in commercial broiler systems.

Introduction

The abuse of antibiotic growth promoters (AGPs) in feed has led to drug resistance and ecological damage would threaten human health eventually. Natural plants have become a hotspot in the research and application of substituting AGPs because of their advantages of safety, efficiency, and availability (Songchang et.al.2021).

Necrotic enteritis (NE), an enterotoxemic disease in poultry, is primarily caused by Clostridium perfringens. The restriction or ban of in-feed antibiotics in regions such as the European Union and China has contributed to a resurgence of NE cases (Shojadoost et.al.2012). The disease is particularly severe in young broilers, with acute mortality rates reaching up to 50%. NE is associated with a significant upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, contributing to systemic immune activation (Lee et.al.2011). As inflammation is metabolically demanding, immune challenges can increase the resting metabolic rate of animals by 8–27%, thereby diverting energy from growth and maintenance processes (Martin et.al.2003).

Inflammation in poultry reduces feed intake, disrupts intestinal morphology, limits nutrient absorption, and redirects energy to immune responses, collectively impairing growth and causing intestinal damage and economic losses (Klasing et.al.1987). Necrotic enteritis (NE) aggravates these effects by inducing gut microbiota dysbiosis, marked by reduced diversity, instability, and enrichment of pro-inflammatory bacteria, which compromise intestinal homeostasis and enhance pathogen persistence (Satokari et.al.2015).

The gut microbiota is the largest symbiotic ecosystem in hosts and has been shown to play an important role in maintaining intestinal homeostasis. Changes in the gut microbiota can confer resistance to pathogenic bacteria or promote infection in a host. A symbiotic microbiome regulates the maturation of the mucosal immune system, while a pathogenic microbiome can cause immune dysfunction in the host, leading to the development of diseases such as intestinal inflammation (Shi et.al, 2017).

Pathogenic bacteria use microbiota-derived carbon and nitrogen sources as nutrients and regulatory signals to promote their own growth and virulence. By inducing inflammation, these bacteria alter the gut environment and use a unique respiratory and metal acquisition system to drive their expansion (Baumler et.al,2016).

Macleaya cordata is a perennial herb widely distributed in southern China and traditionally used in herbal medicine. Its extract (MCE), which contains bioactive alkaloids such as sanguinarine and chelerythrine, was approved as a feed additive in the EU in 2004. Sanguinarine, the major active compound, has demonstrated antitumor (Fu.et.al.2018), immunomodulatory (Kumar et.al.2014), antibacterial (Hamoud et.al.2014), anti-inflammatory (Xue et.al.2017), and insecticidal (Li et.al.2017) properties.

Several investigators have reported that MCE diets could ameliorate production performance, improve gut health and body immunity, and promote growth (Bojjireddy et al., 2013; Khadem et al., 2014). Besides, sanguinarine is the major active ingredient of M. cordata, which has been found to have anti-inflammatory activity (Niu et al.2012), inhibit the activation of NF-κB, and regulate inflammatory response (Wullaert et. al.2011). Gradually, it evoked attention as a substitute of antibiotics (Kim et al.2012). Although sanguinarine is poisonous, an average daily oral dose of alkaloids of up to 5 mg/kg animal body weight has been proven safe (Kosina et al., 2004).

MCE has been reported to modulate intestinal microbiota, particularly in the upper gastrointestinal tract. It promotes beneficial bacteria such as Lactobacillus, inhibits Escherichia coli colonization, and stimulates amino acid, vitamin, and bile acid biosynthetic pathways, while minimizing the risk of antibiotic resistance gene accumulation (Huang et.al.2018). While MCE’s beneficial effects on broiler performance, intestinal integrity, and inflammation have been demonstrated, its impact on humoral immune function and microbiota-mediated amelioration of NE remains insufficiently characterized (Bui et.al.2015).

Dietary supplementation with 100 mg/kg MCE significantly increased the diversity of the microbiota in the ileum of Snowy Peak blackbone chickens, and 200 mg/kg MCE significantly increased the relative abundance of Lactobacillus and Aeriscardovia in the ileum, increased the relative abundance of Bacteroidetes and Deferribacteres in the cecum, and decreased the relative abundance of Firmicutes in the cecum (Guo et.al, 2021).

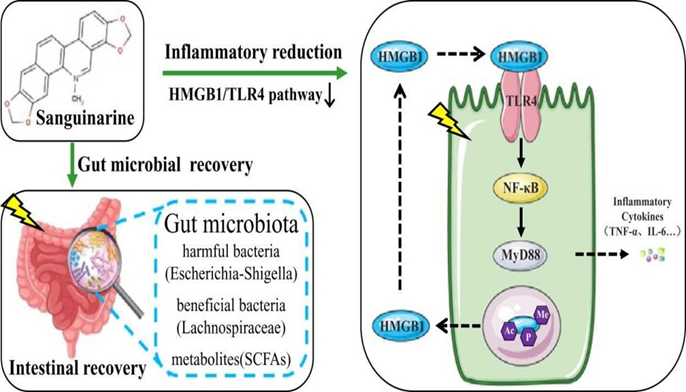

Mechanism of action Macleaya Cordata Extract in poultry gut

1. Inhibition of HMGB1 release and function

HMGB1 is a nuclear protein that acts as a damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) molecule when released from necrotic cells or actively secreted by immune cells. Sanguinarine can interfere with HMGB1’s pro-inflammatory activity in the following ways:

Preventing translocation: Sanguinarine may inhibit the translocation of HMGB1 from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, thereby reducing its extracellular concentration where it acts as an inflammatory mediator.

Direct antagonism: HMGB1 has two binding domains, the A-box and B-box, which interact with various receptors to cause inflammation. Studies show that the HMGB1 A-box can act as an antagonist by competing with full-length HMGB1 for binding sites on TLR4. It’s plausible that sanguinarine may interfere with the binding of the active HMGB1 B-box to its receptor.

2. Interference with TLR4 signaling

TLR4 is a receptor on immune cells that detects inflammatory signals, including extracellular HMGB1. Sanguinarine has been shown to suppress the TLR4 signaling pathway.

Blocking ligand binding: Sanguinarine may directly interact with the TLR4 receptor complex, which includes the protein MD-2. By binding to or otherwise affecting this complex, sanguinarine could prevent the attachment of HMGB1 and other inflammatory ligands like LPS, thus inhibiting the initiation of downstream signaling.

Downregulation of TLR4 expression: Some studies suggest that sanguinarine treatment may lead to the downregulation of TLR4 protein expression on the cell surface, further limiting the cell’s ability to respond to inflammatory signals.

Fig.1. Anti-inflammatory mechanism of Sanguinarine showing reduction of gut lesion by interference of HMGB1/ TLR4 pathway in inflammation site.

3. Suppression of the NF-κB cascade

NF-κB is a key transcription factor that regulates the expression of genes involved in inflammation. Sanguinarine potently suppresses NF-κB activation through several mechanisms.

Inhibition of IκBα phosphorylation and degradation: In resting cells, NF-κB is held inactive in the cytoplasm by its inhibitory subunit, IκBα. Upon cell activation, a kinase complex (IKK) phosphorylates IκBα, leading to its ubiquitination and degradation. Sanguinarine acts upstream of this step, blocking the phosphorylation and subsequent degradation of IκBα. This prevents NF-κB from being released.

Blocking NF-κB nuclear translocation: Because IκBα is not degraded, the NF-κB heterodimer (p65/p50) cannot translocate to the nucleus. This prevents NF-κB from binding to the promoter regions of target genes.

Modification of sulfhydryl groups: A key aspect of sanguinarine’s NF-κB inhibition is its ability to modify critical sulfhydryl groups on proteins in the NF-κB signaling pathway. This covalent modification, which can be reversed by reducing agents like DTT, is thought to be essential for sanguinarine’s inhibitory effect.

4.Resulting anti-inflammatory effects

By inhibiting the HMGB1-TLR4-NF-κB axis at multiple stages, sanguinarine effectively suppresses the inflammatory response.

Reduced cytokine expression: Sanguinarine leads to a decrease in the expression and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β).

Mitigated cellular infiltration: The reduced expression of inflammatory chemokines, such as CCL2, leads to decreased recruitment of inflammatory cells to the site of inflammation.

Protection against tissue damage: These overall effects contribute to the protection of tissues from inflammation-induced injury, as seen in models of renal ischemia-reperfusion injury and ulcerative colitis (Gu. et.al, 2022).

The aim of the study was to evaluate the effect of PHYTOGIC on the performance of commercial broilers reared on deep litter under field conditions.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Design and Management

The trial was conducted at Harsh Broiler House using Vencobb 430 straight run chicks (not sexed at hatchery) in three treatments of around 12000 birds in each treatment. A total of 36000 birds were considered for trial purpose. Feed Formulation used was same for all treatment groups except in T2 where PHYTOGIC was added at 150 gm per ton feed respectively in all stages. (Table 1.) In the study, the energy level was equivalent to the standard requirements of broilers recommended in the Vecobb 430. The trial was carried out over a period of 42 days. The birds were fed ad lib feed and water was available all the times. Care was taken to provide good conditions by adopting strict biosecurity measures. The housing and vaccination procedures were same in both groups.

Table 1. Composition of basal diet for broiler chicks in control group for 3 phases.

| Broiler Feed Formulation (Control) | |||

| Raw Materials | Prestarter | Starter | Finisher |

| Maize | 625.15 | 652.75 | 686.65 |

| HiPro Soya | 335 | 300 | 260 |

| Soya Crude Oil | 6 | 14 | 23 |

| Limestone Powder | 8.5 | 8.5 | 8 |

| Dicalcium Phosphate | 10 | 10 | 8 |

| L Lysine HCI | 2.7 | 2.4 | 2.3 |

| DL Methionine | 3.3 | 3 | 2.7 |

| L Threonine | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Salt | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Soda Bi Carb | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Choline Chloride 60% | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Organic TM | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Broiler Vitamin Premix | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Coccidiostat | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| AGP | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| NSP Enzyme | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Phytase 5000 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Feed Acidifier | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Toxin Binder | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

*The figures are in Kilograms.

The premix provided the following per kilogram of the diet: vitamin A, 6000 IU; vitamin D3, 2500 IU; vitamin B1, 1.75 mg; vitamin B2, 5.5 mg; vitamin B6, 4 mg; vitamin B12, 0.18 mg; vitamin E, 25 mg; vitamin K3, 2.25 mg; Cu, 7.5 mg; Mn, 60 mg; Fe, 75 mg; Zn, 60 mg; Se, 0.15 mg; biotin, 0.14 mg; NaCl, 3.7 g; folic acid, 0.8 mg; pantothenic acid, 12 mg; phytase, 400 U; nicotinic acid, 34 mg; chloride, 350 mg. *Nutrient levels were all calculated values.

Treatment Details-

T1: Control group fed basal diet

T2: Control group fed basal diet + PHYTOGIC @150 g PMT

Parameters Studied-

- Body Weight gain was recorded weekly

- Feed Consumption recorded daily and leftover feed was adjusted in the other day quota to know actual intake.

- Mortality was recorded daily

- EEF calculated post harvesting of the flock

- FCR was calculated every week and post harvesting of the flock.

Results:

Effect of Supplementation of Phytogic on body growth performance parameters like Body Weights, Feed Consumption, FCR and Average Daily gain of Control and Treatment Groups

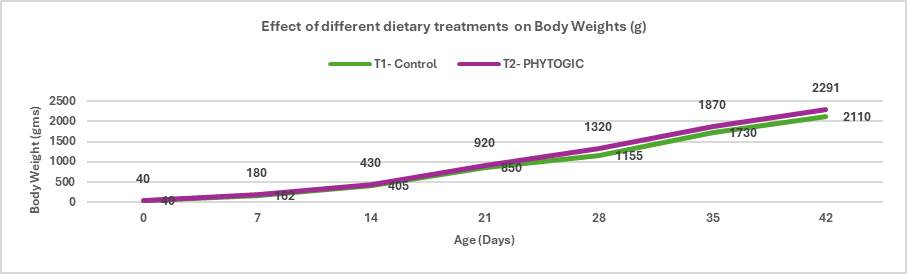

Fig.1. Effect of different dietary treatments on Body Weights (g)

Conclusion: Broilers in the T2 – PHYTOGIC group fed at 150g/ton of feed achieved higher final body weights (2291 g) compared to the T1 – Control group (2110 g), showing an 8.22% improvement. This indicates that PHYTOGIC supplementation effectively enhances growth performance in broilers.

Fig.2. Effect of different dietary treatments on Feed Intake (g)

Conclusion: Broilers in the T2 – PHYTOGIC group fed at 150g/ton of feed consumed more feed (4015 g) compared to the T1 – Control group (3800 g), showing a 5.50% increase in feed intake. This suggests that PHYTOGIC supplementation may enhance feed consumption in broilers.

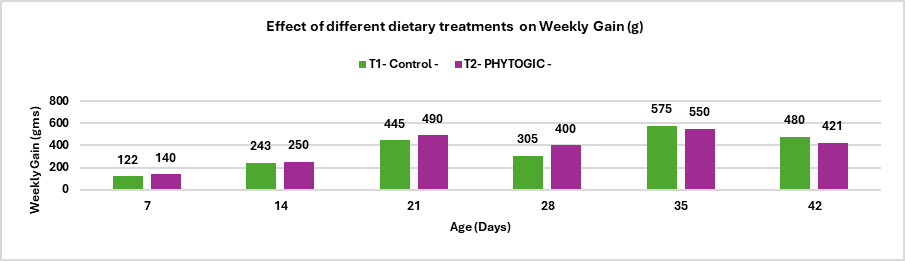

Conclusion: The average weekly percentage difference in weight gain between T2 – PHYTOGIC fed at 150g/ton of feed and T1 – Control was -3.84%, indicating that, overall, PHYTOGIC supplementation did not improve weekly weight gain in broilers and was slightly less effective than the control in this trial.

Fig.4. Effect of different dietary treatments on Feed Conversion Ratio

Conclusion: Broilers in the T2 – PHYTOGIC group fed at 150g/ton of feed showed an improved feed conversion ratio (1.75) compared to the T1 – Control group (1.80), with a 2.81% improvement. This suggests that PHYTOGIC supplementation enhances feed efficiency in broilers, allowing for better weight gain per unit of feed consumed.

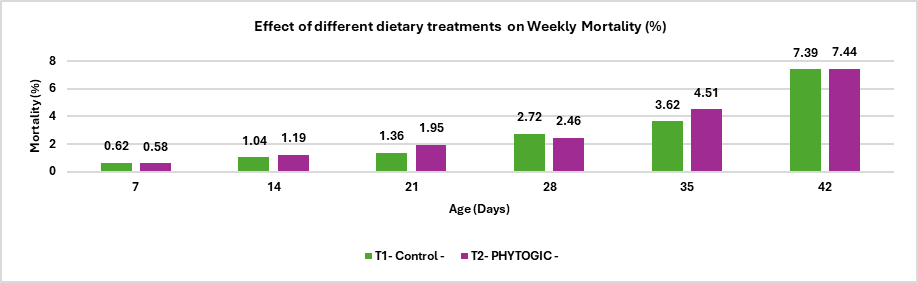

Fig.5. Effect of different dietary treatments on Weekly Mortality (%)

Conclusion:The mortality rate in the T2 – PHYTOGIC group fed at 150g/ton of feed was (7.44%) slightly higher than the T1 – Control group (7.39%), with a 0.27% difference. This minimal variation indicates that PHYTOGIC supplementation had no significant effect on broiler mortality under the conditions of this study.

Table 2. Summary of the Report-

| Parameters | T1- Control | T2- PHYTOGIC | % Difference |

| Body Weight (g) | 2110 | 2291 | 8.22 |

| Feed Intake (g) | 3800 | 4015 | 5.50 |

| FCR | 1.80 | 1.75 | 2.81 |

| CFCR | 1.77 | 1.67 | 5.81 |

| Mortality (%) | 7.39 | 7.44 | 0.27 |

Discussion

The findings of the present field study demonstrate that dietary supplementation with PHYTOGIC at 150 g/ton improved broiler growth performance under commercial deep-litter and heat-stress conditions. Broilers receiving PHYTOGIC exhibited an 8.22% increase in final body weight compared to the control group, indicating enhanced nutrient utilization and metabolic efficiency. This improvement is consistent with previous reports showing that Macleaya cordata extract and its major alkaloid, sanguinarine, can promote growth by reducing intestinal inflammation, stabilizing gut microbiota, and improving nutrient absorption. The observed increase in feed intake (5.50%) in the PHYTOGIC group suggests that phytogenic supplementation may have positively influenced appetite or gut comfort, allowing birds to maintain adequate consumption despite environmental temperature stress.

Feed efficiency was also improved, as evidenced by reductions in FCR (1.75 vs. 1.80) and CFCR (1.67 vs. 1.77). This aligns with earlier studies reporting that sanguinarine-containing extracts suppress inflammatory pathways such as the HMGB1–TLR4–NF-κB axis, thereby reducing metabolic energy waste associated with immune activation. By lowering the inflammatory burden, PHYTOGIC likely allowed more dietary energy to be directed toward growth rather than immune-related maintenance. Improvements in FCR also support the hypothesis that phytogenic compounds enhance gut function through modulation of intestinal morphology and beneficial microbiota populations, as reported in previous research.

Weekly weight gain patterns showed some variation, with PHYTOGIC not consistently outperforming the control in all weeks. This may be attributed to fluctuating heat stress levels and daily feed intake variations typical of field conditions. However, despite these short-term variations, the cumulative performance benefits remained substantial by the end of the production cycle.

Importantly, mortality rates were nearly identical between treatments (7.39% vs. 7.44%), indicating that PHYTOGIC supplementation did not impose any negative health effects and is safe for use under commercial conditions. The lack of impact on mortality also suggests that the performance improvements were not driven by survivability differences but by true enhancement of growth and feed efficiency.

Overall, the results support the potential of PHYTOGIC as an effective phytogenic alternative to antibiotic growth promoters. Its ability to improve growth performance and feed efficiency, even under extreme heat, aligns with its known anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and gut-modulating properties. The findings strengthen the evidence that phytogenic compounds derived from Macleaya cordata can contribute to sustainable poultry production by enhancing physiological resilience and intestinal health.

Conclusion-

The trial was conducted in the extreme heat season where average temperature in the surrounding was around 42-45 degree Celsius. The T2 (PHYTOGIC) groups showed overall improved performance compared to the T1 (Control) group. Specifically, the body weight of T2 (PHYTOGIC) was 8.22% higher than T1 (Control), indicating better growth. Feed Conversion Ratio (FCR) and Corrected FCR (CFCR) were both lower in T2 (PHYTOGIC) by 2.81% and 5.81%, respectively, demonstrating more efficient feed utilization in the T2 (PHYTOGIC) group than T1 (Control). Mortality rates were nearly identical between the two groups, indicating that the supplement did not adversely affect survival. Overall, PHYTOGIC supplementation resulted in better growth performance and feed efficiency compared to the control with no significant impact on mortality.

References:

Bojjireddy N., Sinha R.K., Panda D., Subrahmanyam G. Sanguinarine suppresses IgE induced inflammatory responses through inhibition of type II PtdIns 47kinase(s) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2013; 537:192–197. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2013.07.017.

Bui TP, Ritari J, Boeren S, de Waard P, Plugge CM, de Vos WM. Production of butyrate from lysine and the amadori product fructoselysine by a human gut commensal. Nat Commun. 2015; 6:10062.

Fu C, Guan G, Wang H. The anticancer effect of sanguinarine: A review. Curr Pharm Des. 2018; 24:2760–4.

Hamoud R, Reichling J, Wink M. Synergistic antimicrobial activity of combinations of sanguinarine and edta with vancomycin against multidrug resistant bacteria. Drug Metab Lett. 2014; 8:119–28.

Huang P, Zhang Y, Xiao K, Jiang F, Wang H, Tang D, et al. The chicken gut metagenome and the modulatory effects of plant-derived benzylisoquinoline alkaloids. Microbiome. 2018; 6:211.

Khadem A., Soler L., Everaert N., Niewold T.A. Growth promotion in broilers by both oxytetracycline and Macleaya cordata extract is based on their anti-inflammatory propertiese. Br. J. Nutr. 2014; 112:1110–1118. doi: 10.1017/S0007114514001871.

Kim J.C., Hansen C.F., Mullan B.P., Pluske J.R. Nutrition and pathology of weaner pigs: Nutritional strategies to support barrier function in the gastrointestinal tract. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2012; 173:3–16.

Klasing KC, Laurin DE, Peng RK, Fry DM. Immunologically mediated growth depression in chicks: Influence of feed intake, corticosterone and interleukin-1. J Nutr. 1987; 117:1629–37.

Kosina P., Walterova D., Ulrichova J., Lichnovsky V., Stiborova M., Rydlova H., Vicar J., Krecman V., Brabec M.J., Simanek V. Sanguinarine and chelerythrine: assessment of safety on pigs in ninety days feeding experiment. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2004; 42:85–91. doi:

Kumar GS, Hazra S. Sanguinarine, a promising anticancer therapeutic: Photochemical and nucleic acid binding properties. RSC Adv. 2014; 4:56518–31.

Lee KW, Lillehoj HS, Jeong W, Jeoung HY, An DJ. Avian necrotic enteritis: Experimental models, host immunity, pathogenesis, risk factors, and vaccine development. Poult Sci. 2011; 90:1381–90.

Li JY, Huang HB, Pan TX, Wang N, Shi CW, Zhang B, et al. Sanguinarine induces apoptosis in eimeria tenella sporozoites via the generation of reactive oxygen species. Poult Sci. 2022; 101:101771.

Martin LB 2nd, Scheuerlein A, Wikelski M. Immune activity elevates energy expenditure of house sparrows: A link between direct and indirect costs? Proc Biol Sci. 2003; 270:153–8.

Niu X., Fan T., Li W., Xing W., Huang H. The anti-inflammatory effects of sanguinarine and its modulation of inflammatory mediators from peritoneal macrophages. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2012; 689:262–269. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.05.039.

Satokari R. Contentious host-microbiota relationship in inflammatory bowel disease–can foes become friends again? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015; 50:34–42.

Shojadoost B, Vince AR, Prescott JF. The successful experimental induction of necrotic enteritis in chickens by clostridium perfringens: A critical review. Vet Res. 2012; 43:74.